Jean DUPONT

Dieses Dokument ist Teil der Anfrage „Operational Plans for Joint Operation Poseidon 2018 and 2019“

Recommendation on issues related to how the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) communicates with citizens in relation to its access to documents portal (Joined Cases 1261/2020 and 1361/2020) 1 Made in accordance with Article 4(1) of the Statute of the European Ombudsman The case concerned primarily Frontex’s decision not to communicate any more by email with applicants who request public access to documents. Frontex obliges citizens to use its online access portal. This causes a number of unnecessary problems for individual applicants as well as for transparency platforms that civil society organisations have set up to help further the EU’s aim of working as openly as possible. The Ombudsman could not find justifications for Frontex’s decision. She therefore issues a recommendation that Frontex should allow applicants to communicate with it by email, in full and without resort to its current access to documents portal. The Ombudsman moreover suggests that Frontex should dedicate the resources that are required for handling the large number of access requests that it is likely to receive on a regular basis going forward. Background to the complaints 1. In January 2020, Frontex introduced a new system for handling requests for public access to documents. The new system requires an applicant to log in to an account/space that is created for the application. 2. The complainants in this case were concerned about several aspects of the new system and related practices. 1 Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal- content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2021.253.01.0001.01.ENG&toc=OJ%3AL%3A2021%3A253%3ATOC Brussels Strasbourg Postal address + 33 (0)3 88 17 23 13 Rue Froissart 87 Havel Building - Allée Spach 1 Av. du Président R. Schuman ombudsman.europa.eu B-1000 Bruxelles F-67000 Strasbourg CS 30403 F-67001 Strasbourg Cedex

3. The main issue was Frontex’s decision to oblige applicants to use its new access portal and not to communicate with applicants by email any more 2. 4. One consequence of this decision is that the communications and documents that Frontex sends to applicants can no longer be published automatically on online transparency portals that European civil society organisations have created to further the openness of the EU administration 3. This is because their automatic publication technically depends on the communication being done by email. The complainants argued that Frontex’s decision is not in line with the European Ombudsman’s finding in case 104/2020/EWM: "Fulfilling requests via online [transparency] portals is an effective means of complying with [the] obligation [to give the fullest possible effect to the right of access and take into account the public interest in the wider disclosure of documents requested] . Where an applicant has specifically stated that this is their preferred medium for receiving the response to their request and any documents to which public access is granted, institutions should comply with that request unless there is very good reason (which should be explained) for them not to do so. This is a matter of good administration as well as a means of complying with the legal obligation to give the widest possible publ ic access." (Paragraph 11 4. 5) 5. The complainants also referred to the fact that refusing to communicate with applicants by email is unusual. The EU administration, and notably the original addressees of the EU’s transparency regulation (Parliament, Council and Commission), normally communicate with applicants by email. 6. The complainant moreover pointed to the following issues: 1) When Frontex disclosed documents, it referred systematically to ‘copyright’ and stated that it prohibited the applicant from making the documents available to third parties without its authorisation. 6 2 Frontex merely uses email communications to notify applicants whenever there is new content on the access account. When this happens the applicant receives a link to the access account with a hyperlink, and then has to go through a cumbersome process to access the content in question. 3 asktheeu.org: https://www.asktheeu.org/en, established in 2011. For an example of how it works, see: https://www.asktheeu.org/en/request/letters_to_commission_and_counci#outgoing-21623 It is based on a system that is now used in 25 jurisdictions around the world: http://alaveteli.org/deployments/ FragDenStaat, https://fragdenstaat.de, also established in 2011. For an example of how it works, see: https://fragdenstaat.de/anfrage/klimawandel-5/ 4 https://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/decision/en/124793 5 To see how Frontex’s practice results in a message that asks the applicant to log on to the access account, as opposed to providing the document as such (“New information regarding your application is available under this link”), see: https://www.asktheeu.org/en/request/correspondence_between_frontex_r#incoming-36989 To see how staff at a transparency site have had to upload the documents manually that Frontex made available in the access account only, see: https://fragdenstaat.de/anfrage/frontex-social-media-guidelines/#nachricht-574618 6 On the issue of copyright, Frontex’s internal decision regarding public access to documents merely provides that “This Decision is without prejudice to any existing rules on copyright which may limit a third party’s right to reproduce or exploit disclosed documents” (Article 16). In its replies to citizens requesting public access, it systematically included this message: “Kindly be reminded that the copyright of the document/s rests with Frontex and making this/these work/s, available to third parties in this or another form without prior authorisation of Frontex is prohibited.” 2

2) Frontex blocked access to the account created for requests 15 days after it had sent its initial reply. 7. The complainants expressed concerns as to whether Frontex had intentionally introduced practices that compromise the exercise of the fundamental right of public access to documents. The Ombudsman's proposal for a solution 8. In her solution proposal of May 2021, the Ombudsman made the following findings regarding the main issue, that is, Frontex’s decision not to communicate any more by email (emphasis added): “[Frontex’s] new public access portal appears not to provide for the option of receiving Frontex’s reply and documents directly by email. In addition to constituting a new hurdl e for individuals, this reduces the seamless technical communication with some online transparency platforms operating in Europe.” “Frontex should, when it receives requests for public access to documents through civil society platforms or when it is otherwise the express wish of an applicant, send its replies by e-mail and not through its public access portal. This means that the actual reply to a request for access to documents or to a confirmatory request - and not only a notification to access Frontex’s public access portal - should be sent to an applicant by e-mail, unless there is a very good reason (which should be explained) for Frontex not to do so.” 9. In addition to this, the Ombudsman proposed that Frontex should no longer use the copyright statement it was then using, and that it should ensure that documents in its public access accounts are available for at least two years. The Ombudsman moreover noted the following possibility for improvement: Frontex could, in its replies, indicate a dedicated email address through which applicants can submit appeals against non- disclosure (‘confirmatory application’). 10. Frontex implemented the Ombudsman’s proposals to revise its copyright statement 7 and to make documents in its public access accounts available fo r two years. It also agreed to introduce a dedicated email address for submission of appeals. 11. Frontex continues, however, not to communicate substantively with applicants by email. It uses emails merely as a means of drawing applicants’ attention to new c ontent on the access portal, which they then have to log in to. 12. Frontex suggested, in summary, that it would have problems managing public access applications (processing, deadlines...) if it had to send its replies and disclose documents by email. 7 The copyright notice, which the Ombudsman has accepted, now reads as follows: “S ubject to any intellectual property rights of third parties, the document/s may be reused provided that the source is acknowledged and that the original meaning or message of the document/s is not distorted. Frontex is not liable for any consequence resulting from the reuse of this/these document/s.” 3

13. In response to the Ombudsman’s observation that other EU institutions appear to work differently, it described its new system as being a “bespoke solution” that helps to “achieve administrative fairness for both applicants and Frontex”. The Ombudsman's assessment after the solution proposal 14. The Ombudsman welcomes Frontex’s implementation 8 of her proposals referred to in paragraph 9 above. 15. The Ombudsman regrets that Frontex did not implement her proposal that Frontex should - when expressed or implicitly asked - communicate substantively and directly with applicants by email. Frontex still does not send applicants its content-messages and documents by email. 16. The Ombudsman has not received convincing explanations for this choice. On the contrary, the Ombudsman is most concerned about the vagueness of Frontex’s response (‘administrative fairness for Frontex’). 17. The Ombudsman is aware that Frontex receives many requests for access to documents, and that some requests concern many documents. 18. Intense interest in Frontex’s work is, however, inherent to the nature of its core activities. Frontex is directly involved in highly sensitive activities that impact on the fundamental and human rights of people who are often in precarious situations. It is therefore to be expected that Frontex will receive many requests for public access to its documents. It is for Frontex to dedicate the necessary resources to meet this task. 19. The EU’s transparency regulation is an instrument with democratic objectives, introduced on the conviction that openness helps the public administration to “enjoy greater legitimacy and is more effective and more accountable to the citizen in a democratic system” 9. It imposes on the EU administration the obligation to grant the widest possible public access to its documents and to do so in accordance with principles of good administration, for instance by providing the most service-minded environment possible. 20. When EU institutions take measures to implement their obligations under the transparency regulation, an important starting point are the best practices that are already being implemented in the EU administration 10. 8 This was not mentioned as such in Frontex’s reply to the solution proposal, but came about following subsequent exchanges with the Ombudsman’s inquiry team. 9 Recital 2. 10 Article 15 of the regulation: “Administrative practice in the institutions 1. The institutions shall develop good administrative practices in order to facilitate the exercise of the right of access guaranteed by this Regulation. 2. The institutions shall establish an interinstitutional committee to examine best practice, address possible conflicts and discuss future developments on public access to documents.” 4

21. The complainants in the present case have rightly pointed out that a decision not to communicate any more with applicants by email does not reflect a general or best practice in the EU administration. 22. Over the years, the EU institutions have taken both administrative and technical measures to enable the smoothest possible communication with the civil society transparency portals referred to above. In particular the three main institutions follow a clear policy of making it possible for those platforms to function properly. They have accepted that, by doing so, any member of the public can follow their processing of access requests online. 23. Emails are one of the most important electronic communication tools. Frontex has taken a decision of major importance by deciding not to communicate with applicants by email any more. It did so while being aware of the negative consequences that this would have for the citizens who legitimately use the above-mentioned civil society portals. 24. In light of the above considerations, the Ombudsman concludes that it is maladministration not to offer citizens the possibility of communicating with it by email in relation to their requests for public access to documents. The Ombudsman therefore issues a corresponding recommendation. Recommendation The Ombudsman makes the following recommendation: Frontex should ensure seamless technical communication with applicants for public access to documents, allowing them to communicate with it by email in full and without resorting to its current access to documents portal. In examining this recommendation, Frontex should inform itself of the best practices that the European Commission has identified in its current project to introduce a public access portal, and implement such best practices as soon as possible. Frontex and the complainant will be informed of this recommendation. In accordance with Article 4(2) of the Statute of the European Ombudsman, Frontex shall send a detailed opinion by 21 September 2022. Suggestions for improvement Frontex should dedicate the resources that are needed for handling the predictably large number of access requests that it is likely to receive on a regular basis going forward. Frontex should draw up a detailed manual on how it handles public access requests, and publish that manual. 5

Strasbourg, 21/06/2022 Emily O’Reilly European Ombudsman 6

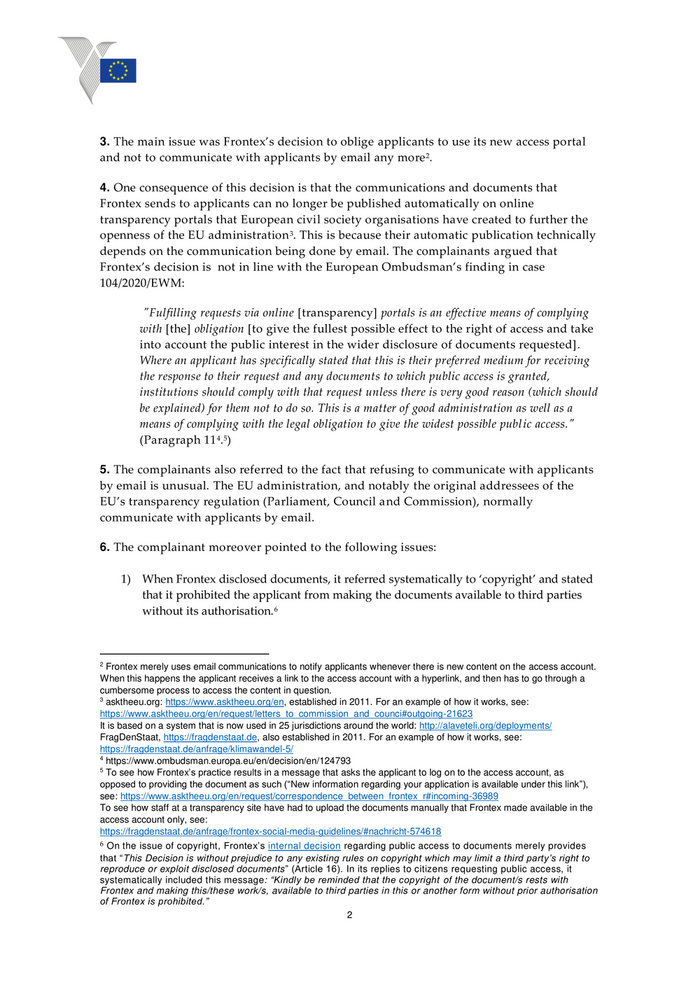

ANNEX 1. The Ombudsman is not convinced that Frontex’s public access portal provides for the kind of easy and user-friendly communication that must be provided under the transparency regulation. It seems reasonable to expect that a citizen would have a single account that s/he could keep open and within which correspondence (email/message like) regarding the request would take place. With Frontex, one account is created for each request, and for every communication one has to log on to see the content of the request. The required log-on data is excessive (see picture below), a fact that is inexplicable in light of the fact that the documents here concerned are public. 2. The Ombudsman also notes that Frontex has seemingly disregarded readily available solutions for combining dedicated portal-systems with email communication. For many years now, commonly used IT-systems have allowed for a seamless integration of emails into ‘account’ or ‘portal’ systems. This applies to incoming as well as outgoing communications. It is a common IT function to make it possible to send emails ‘out of’ an account. Similarly for incoming emails, an add-on (a small computer programme) in the email system can allow support staff to integrate rapidly a new email into the account in question. A whole host of configuration and programming options are available nowadays for such functions to be adapted to an organisation’s needs, including for internal visibility and checking of deadlines. In short, ‘portal’ or ‘account’ systems can be integrated wi th email systems. 3. Even when the number of documents to be sent goes beyond the reception-limit of email accounts - which, however, go to several hundred pages - there are straightforward solutions for rapidly producing and providing a link to an online se rver (‘cloud’) from which the documents can be downloaded. 4. At any rate, the complexity of the processes here concerned is very low, and cannot justify abandoning the use of emails. There is normally just one external party to communicate with, the object of the communication is relatively limited in scope (one or more documents), the process is linear and chronological, and the deadlines are well defined. 7